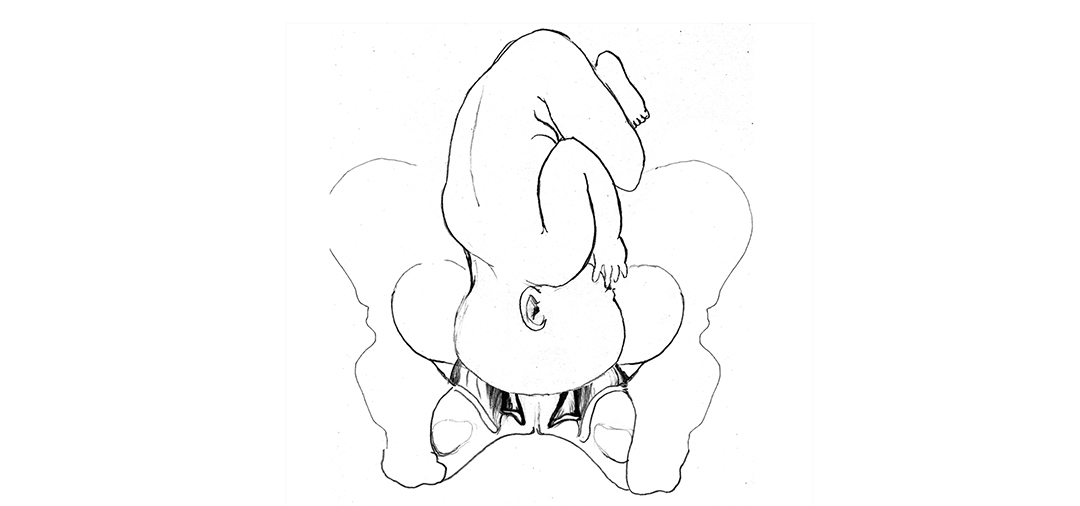

Last week I mentioned the effect on babies from entering into the pelvis from the right side. Some babies take longer to engage and some need to rotate before they can engage. This seems to have to do with head circumference and whether baby can slip into the pelvis or is waiting above the symphysis, unable to navigate the forehead past the bone. Rotation becomes the key to unlock a vaginal birth. But what helps rotation?

The Spinning Babies® view is that the baby coming from the left has more chance of flexion. Flexion allows the smallest diameters of the baby to move through the pelvis.

More babies enter the pelvis in a deflexed presentation when coming into the pelvis from the mother’s right side. This means the chance of the baby’s chin being lifted is higher. When the chin is up the baby is deflexed or extended.

Why? There are theories surrounding maternal anatomy and rotation to a posterior presentation. Some say the liver is on the right towards the front of the body, some say the descending colon is on the left in back. There is likely some effect from these facts. Going back to the medical literature of the era around the 1890s to the 1940s finds mention of the uterus having a shape called right obliquity. Details of how the baby, even the head down baby, lie in the womb could be due to right obliquity.

It’s important to know that a baby lying in the womb on the right side is not a mirror image of the baby who is on the left, just as the posterior baby is not a mirror image of the anterior baby. When a labor lingers, this mistaken belief reduces a provider’s tendency to act before early signs of distress. Meanwhile, the position itself is an invitation to act.

Head flexion creates a smaller head circumference to fit the pelvis more comfortably, to optimize molding, and to allow the baby to use their spine to navigate pelvic space during and between contractions. A tucked chin allows the wider part of the head to enter the pelvic floor first, increasing flexion for rotation and descent through the outlet.

Extension puts the fetal spine at its longest so that some fetal maneuverability is reduced. The baby can’t help in the birth as much. A larger diameter of the fetal head enters the pelvis when the chin is up. The forehead may come upon the pelvic floor before the parietal eminence and turn the baby to the direct occiput posterior position.

My grandchildren demonstrate the head angles of flexion, deflexion, and extension (right-left) in this photograph of them sleeping together.

Right obliquity is the theory accepted by Spinning Babies® as the leading determinate of why the baby entering from the right may present deflexed and rotation more often (but not always) to the direct posterior. The roundness of the uterus on the maternal left may enhance flexion for the baby entering the pelvis from the left, even when Left Occiput Posterior. Rotation to occiput anterior is more likely.

The old literature supports these theories. New literature since 2005 has not, simply because a single variable is popular to research. Comparing only posterior-anterior fetal positions doesn’t completely explain the mystery of birth ease. Station and flexion are since being researched as variables in birth outcomes.

Spinning Babies puts together the multivaried details of fetal presentation, especially as a reflection of the state of the birth anatomy to answer the question, “Why are some births easier than others?”

“Where’s baby?” is a simple question to answer the complexity of fetal position, presentation, flexion/extension, station, synclitism/asynclitism for the purposes of labor progress.

References at SpinningBabies.com

[tribe_events_list limit=”4″]

One of our most beloved products, now with subtitles in English, French, and Spanish, offering expert support to reduce intervention and increase comfort throughout pregnancy and birth.